Using HttpClient to Consume ASP.NET Web API REST Services

So you installed the ASP.NET MVC 4 Beta and followed the Web API introduction over at the ASP.NET website. Great! You now have a nice HTTP based API that plays nicely with jQuery and other client side JavaScript libraries, and even other server-side technologies. But how exactly do we perform server side consumption of that API in .NET?

**UPDATE**

I updated the post and the examples with the full code for making GET’s, POST’s, PUT’s, and DELETE’s. I didn’t have much time, so let me know if there are any mistakes/issues.

Let’s say that you want to build an uber-flexible n-tier architecture for your next great app. One option for decoupling your layers is to build them as web services. That way you not only decouple the code relationships, but you decouple the platforms as well.

For example, if you build your BLL (Business Logic Layer) as a web service any platform can interact with it. Your presentation layer can be a MVC site, a WPF app, a mobile app, or anything else you can think up. The only requirement is that the front end be able to reach the web service and correctly talk to it.

Where’s the meta data???

How are we going to generate the proxy classes for this new web service??? I’m not going to lie and say that your old friend the “Add Service Reference…” dialog is going to be able to help you out here. Because this is a simple HTTP based API, no meta data gets generated about the API itself (at least as far as I know, and at the time of writing this post).

While I love the “automagical” nature of the “Add Service Reference…” dialog, it always scared me a little bit. It hid a lot of code and required an active instance of the web service to be up and running somewhere (locally was fine). Now, we have complete control over the serialization and deserialization of the data and can write more testable code (more on that later).

Show me the frickin’ code!

Attached is a working sample solution that demonstrates my examples below.

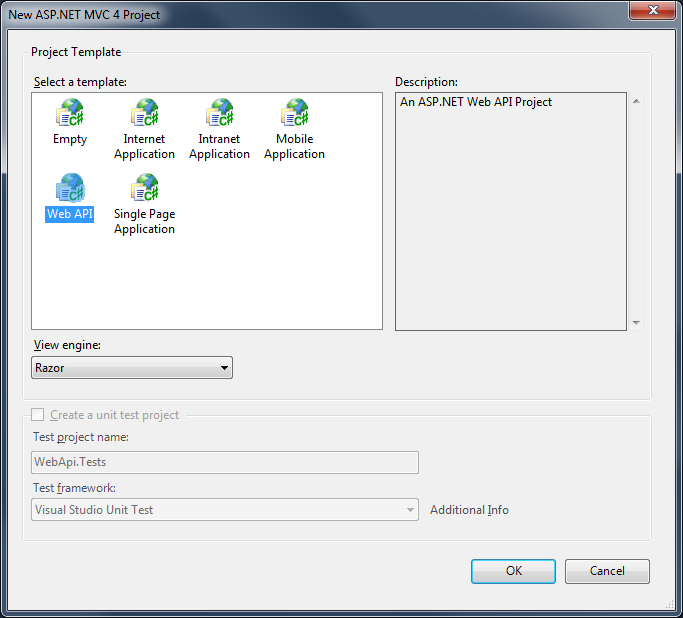

First, create a new ASP.NET MVC 4 project and select the Web API template. I called mine “WebApi”:

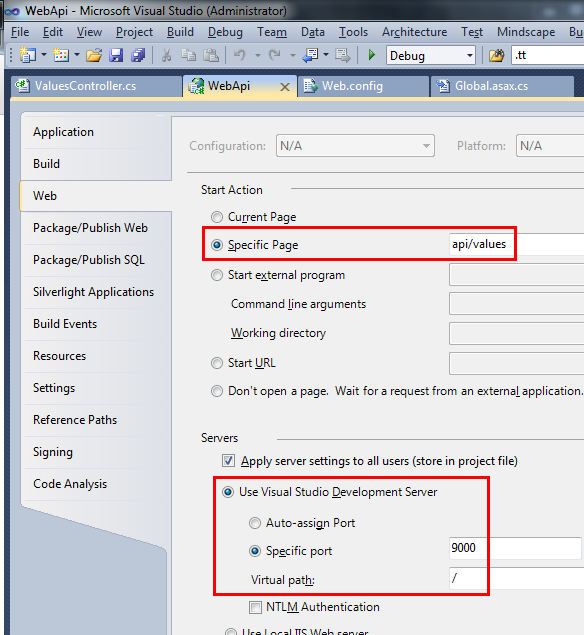

After the solution loads let’s make sure that our web service is in an accesible location. Open up the project Properties > Web and then set the Specific Page to be “Values” and the Specific Port to be 9000. We’ll reference that port in our test consumer in a minute:

You can test out the default API by just hitting F5. The local web service URL (http://localhost:9000/api/values) should open in your default browser and you should see some XML (The styling may be different in your browser):

<string>value 1</string>

<string>value 2</string>

(Note: If you want to see the JSON, you can send an HTTP “Accept Header”. The Web API will see this and spit back your data serialized to JSON. Make sure you use this header when making requests from jQuery. Check out the ASP.NET Web API Introduction for an example, or use Fiddler.)

When you ran your project, a route defined in the Global.asax sent your request to the ValuesController in the Controllers folder. In the ValuesController, the request matched the first action via the HTTP request method verb and the parameters. To see this in action try going to http://localhost:9000/api/values/5. Additionally, requests can be mapped by name too.

So far so good. Let’s spice up the API a little bit and return our own custom type. Create a new class library project within your solution. I called mine “WebApi.Dal”. Rename the deafult “class1.cs” to “MyDataClass.cs” and let Visual Studio auto update the references. Now add some properties. Mine ended up like this:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

namespace WebApi.Dal

{

public class MyDataClass

{

public string MyProperty1 { get; set; }

public bool MyProperty2 { get; set; }

public int MyProperty3 { get; set; }

public decimal MyProperty4 { get; set; }

}

}

Now let’s switch back to the Web API project. Add a reference to your DAL project and replace the first controller action with this one:

// ... usings, namespace and class/controller declarations.

// GET /api/values

public MyDataClass Get()

{

return new MyDataClass

{

MyProperty1 = "Property 1", // String

MyProperty2 = true, // Bool

MyProperty3 = 987654, // Integer

MyProperty4 = 100.87m // Decimal

};

}

// Rest of the class/controller definition...

Now run the solution again and you should see this:

<mydataclass xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xmlns:xsd="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema">

<myproperty1>Property 1</myproperty1>

<myproperty2>true</myproperty2>

<myproperty3>987654</myproperty3>

<myproperty4>100.87</myproperty4>

</mydataclass>

Great! Piece of cake! Now back to the problem at hand.

Consuming the Web API Service

Back in Visual Studio create a Console Application project. I called mine “WebApi.Tester”. Add a reference to the WebApi.Dal project, but you don’t need to add one to the WebApi project. Having access to the classes that were used to serialize the Web API data will allow us to deserialize the data easily, and we don’t need any “direct” relation to the web service itself, just the data it provides.

In the Nuget Package Manager search for System.Net.Http and install the package that matches that name (a bunch of other results show up, but get the one from Microsoft) and the one that matches the name with “Formatter” on the end.

Then search for “json” and add the Json.NET package from Newtonsoft.

Then Add a Reference to System.Net.Http.Formatting and System.Json.

Now you should now have references to:

- Newtonsoft.Json

- System.Json

- System.Net.Http

- System.Net.Http.Formatting

- System.Net.Http.WebRequest

- WebApi.Dal

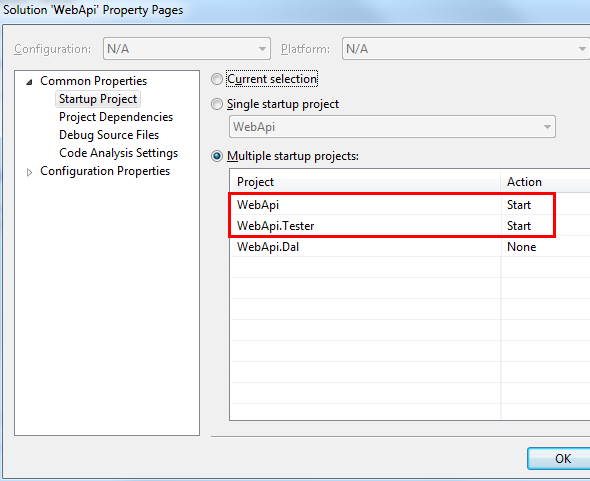

When we go to test this setup, we want both the WebApi MVC project to run, as well as the WebApi.Tester Console app. To do that, open up the Solution Properties, check the radio button that says “Multiple startup projects”, and set WebApi and WebApi.Tester as startup projects:

Now we are ready to write some code. Here is a base client class I whipped up that provides a generic interface to the Web API service:

public class BaseClient

{

protected readonly string _endpoint;

public BaseClient(string endpoint)

{

_endpoint = endpoint;

}

public T Get()

{

using (var httpClient = new HttpClient())

{

T result = default(T);

Task responseTask = null;

httpClient.GetAsync(_endpoint).ContinueWith((requestTask) =>

{

responseTask = requestTask;

HttpResponseMessage response = requestTask.Result;

response.EnsureSuccessStatusCode();

response.Content.ReadAsAsync().ContinueWith((readTask) =>

{

result = readTask.Result;

});

});

// HACK: My version of the await keyword

while (responseTask == null || !responseTask.IsCompleted || result == null) { }

return result;

}

}

}

(Important: As of this writing, the above code may fail. Keep reading for a solution.)

So about that code above… it doesn’t always work… It appears that there is some issue with the deserializer and I get the following exception when reading the result from the inner async method:

“The input stream contains too many delimiter characters which may be a sign that the incoming data may be malicious.”

Basically, there is some sort of “security” measure in place in case the data is too big and there are too many delimiters.

Not to worry, I got your back! Just substitute that inner async call with this one, which delegates the deserialization to the Newtonsoft JSON library!

response.Content.ReadAsStringAsync().ContinueWith((readTask) =>

{

result = JsonConvert.DeserializeObject(readTask.Result);

});

I asked about the above issue on the official ASP.NET forums and I got a response on this thread. It looks like you just need to set the SkipStreamLimitChecks static property to true on the MediaTypeFormatter class. As of this writing, I haven’t tested that solution but I left the commented samples intact in case you want to give it a go.

But let’s be honest with eachother. You think that code is ugly. It is ugly, it’s not just you. So I started another thread about how to reign that code in and clean it up. I got a great response from a guy in this thread. Since the async code is so ugly in .NET 4, and in my case it wasn’t really needed, I left it out. So the first return is the one that executes in the example and it’s still using Newtonsoft JSON:

public T Get()

{

using (var httpClient = new HttpClient())

{

var response = httpClient.GetAsync(_endpoint).Result;

// This works:

return JsonConvert.DeserializeObject(response.Content.ReadAsStringAsync().Result);

// This may not work:

return response.Content.ReadAsAsync().Result;

// This may not work:

return response.Content.ReadAsOrDefaultAsync().Result;

}

}

So now my code is a lot shorter, cleaner and easier to grok. For now we’re basically skipping the async stuff, but I think that’s a smart decision until we can leverage the await keyword and all it’s compiler magic. For a quick sample of how the await keyword in .NET 4.5 relates to the Web API, check out this post by the architect behind all this stuff, Henrik F Nielsen.

Sample Solution

I threw together a simple sample solution that is a complete working example. Nuget package restore is enabled and I removed all the packages to make the zip file as small as possible. The first build of the solution will take a minute because it has to go fetch all the packages and their dependencies. Let me know if you have any problems running the code.

Web API with HttpClient Sample Solution

In case you don’t feel like downloading the zip, the full relevant code from the solution is below:

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Net.Http;

using System.Net.Http.Formatting;

using System.Net.Http.Headers;

using Newtonsoft.Json;

using Newtonsoft.Json.Converters;

public class BaseClient

{

protected readonly string _endpoint;

public BaseClient(string endpoint)

{

_endpoint = endpoint;

}

public T Get<t>(int top = 0, int skip = 0)

{

using (var httpClient = new HttpClient())

{

var endpoint = _endpoint + "?";

var parameters = new List<string>();

if (top > 0)

parameters.Add(string.Concat("$top=", top));

if (skip > 0)

parameters.Add(string.Concat("$skip=", skip));

endpoint += string.Join("&", parameters);

var response = httpClient.GetAsync(endpoint).Result;

return JsonConvert.DeserializeObject<t>(response.Content.ReadAsStringAsync().Result);

}

}

public T Get<t>(int id)

{

using (var httpClient = NewHttpClient())

{

var response = httpClient.GetAsync(_endpoint + id).Result;

return JsonConvert.DeserializeObject<t>(response.Content.ReadAsStringAsync().Result);

}

}

public string Post<t>(T data)

{

using (var httpClient = NewHttpClient())

{

var requestMessage = GetHttpRequestMessage<t>(data);

var result = httpClient.PostAsync(_endpoint, requestMessage.Content).Result;

return result.Content.ToString();

}

}

public string Put<t>(int id, T data)

{

using (var httpClient = NewHttpClient())

{

var requestMessage = GetHttpRequestMessage<t>(data);

var result = httpClient.PutAsync(_endpoint + id, requestMessage.Content).Result;

return result.Content.ReadAsStringAsync().Result;

}

}

public string Delete(int id)

{

using (var httpClient = NewHttpClient())

{

var result = httpClient.DeleteAsync(_endpoint + id).Result;

return result.Content.ToString();

}

}

protected HttpRequestMessage GetHttpRequestMessage<t>(T data)

{

var mediaType = new MediaTypeHeaderValue("application/json");

var jsonSerializerSettings = new JsonSerializerSettings();

jsonSerializerSettings.Converters.Add(new IsoDateTimeConverter());

var jsonFormatter = new JsonNetFormatter(jsonSerializerSettings);

var requestMessage = new HttpRequestMessage<t>(data, mediaType, new MediaTypeFormatter[] { jsonFormatter });

return requestMessage;

}

protected HttpClient NewHttpClient()

{

return new HttpClient();

}

}